Salt Under Pressure: How Flawed Science Shaped Global Sodium Policy

Decades of dietary guidance rest on a shaky foundation. A closer look at the INTERSALT Study, sodium biology, and the science behind the limits.

Salt is under fire. But the case against it rests on shaky ground.

Despite decades of public health messaging, scientific consensus around sodium and blood pressure is far from settled. New evidence, re-analyses of old studies, and a deeper understanding of human physiology are all pushing the debate in a new direction: one that favors individualized nutrition over one-size-fits-all sodium limits.

Salt has long been central to human survival. The word "salary" stems from salarium, a Roman soldier’s salt allowance—an early sign of salt's value. Historical consumption was high: pre-industrial diets, particularly in Europe, often included 40–50 grams of salt per day, largely due to preserved fish and meats. Today, Westerners average roughly half that, yet are warned that it’s too much.

Why the disconnect?

Much of modern salt policy originates with the 1988 INTERSALT Study. This large epidemiological project tracked sodium intake and blood pressure across 52 populations. The study’s conclusions—that higher sodium correlated with increased age-related blood pressure—became the foundation for global sodium limits, now typically set at or below 2,300 mg/day.

But the study had major flaws. It included only four ultra-low-sodium groups, like the Yanomami tribe, whose data heavily skewed results. Sodium intake was measured using single-day 24-hour urine collections—now widely considered unreliable. Confounders were inconsistently adjusted for, and the handling of outliers was later criticized. When reanalyzed with these issues corrected, the correlation between sodium and blood pressure weakened significantly. Still, policy had already been set.

Meanwhile, biology tells a different story. The kidneys can excrete up to 900 grams of sodium daily—far beyond typical dietary levels. When sodium is restricted, the body compensates by activating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), signaling salt cravings and conserving sodium. If intake falls too low, hyponatremia can result—leading to fatigue, nausea, confusion, and even seizures. These effects are well-documented in endurance athletes and those on overly restrictive diets.

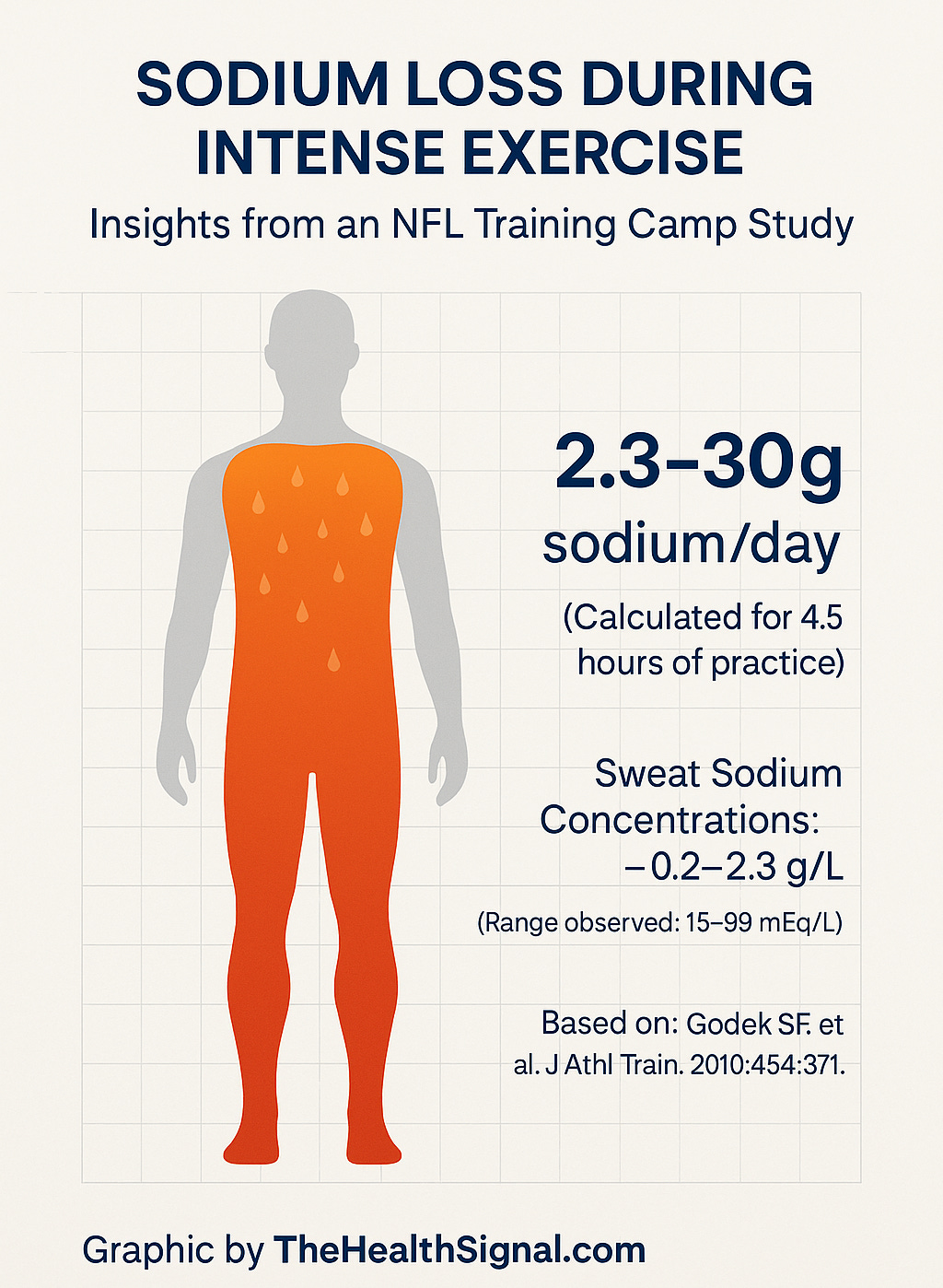

A 2010 study of Philadelphia Eagles players found sodium losses through sweat ranging from 2.3 to 30 grams per day. Most athletes failed to replace these losses through food alone. This variability highlights that sodium needs depend heavily on lifestyle and environment.

Epidemiological evidence now suggests the relationship between sodium and heart health is U-shaped or J-shaped: both very high and very low sodium intakes are associated with greater cardiovascular risk. The optimal intake range appears to fall between 2,600 and 5,000 mg/day—significantly higher than current guidelines. Additional evidence here.

Public health policies often attribute high sodium intake to processed foods. But salt is rarely the root cause of health issues. Processed foods also contain added sugars, industrial seed oils, and preservatives—ingredients with clearer ties to chronic disease. Blaming salt oversimplifies the problem and may mislead consumers.

Sodium is a vital nutrient, tightly regulated by the body. The fear surrounding it stems more from flawed studies and outdated assumptions than from consistent scientific evidence. As research evolves, a shift toward personalized, context-aware nutrition is not only justified—it’s overdue.

Coming next in Part Two: Salt Sensitivity and Metabolic Health—Who Really Needs Less Sodium?