The Fiber Gap: A Growing Threat Behind America's Rising Colon Cancer Rates

The Cancer-Fiber Disconnect: How a Preventable Deficiency Is Hitting a New Generation Hard

Colorectal cancer is climbing fast among young adults. At the same time, Americans are eating half the recommended amount of fiber. The link between these trends is more than nutritional trivia — it may be a major public health blind spot.

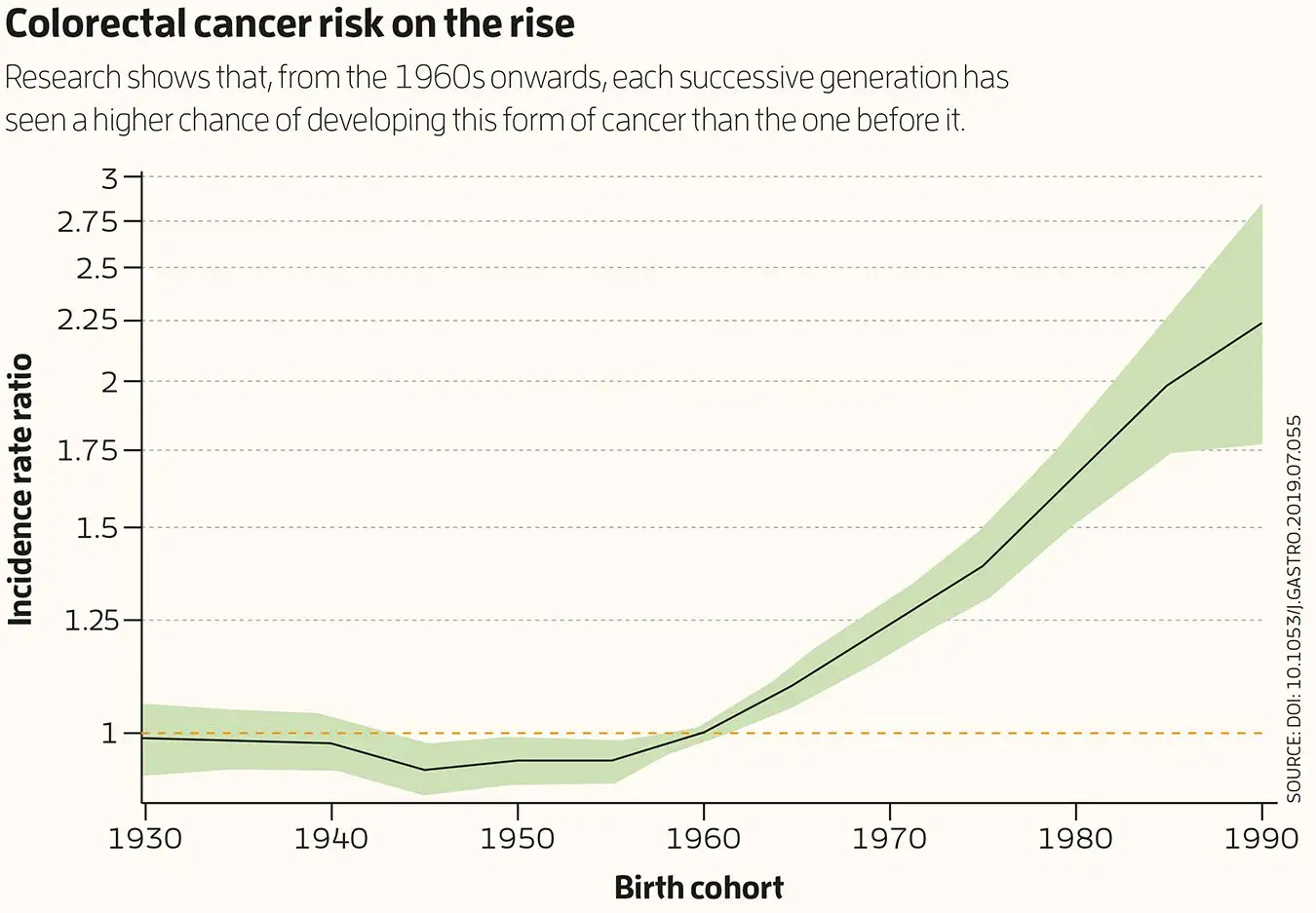

The latest national data show colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the deadliest cancers in the U.S. But a closer look reveals something new: rates are declining among older adults while rising sharply in people under 50. In fact, CRC cases in people aged 15 to 19 have grown more than 300% since 1999.

This generational shift has already prompted earlier screening recommendations, now starting at age 45. But some doctors warn even that may be too late.

“We’re seeing patients in their 30s and even 20s,” said Dr. Kimmie Ng, director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “And in many cases, diet is playing a big role.”

Fiber: The Anti-Cancer Nutrient Most Americans Lack

Fiber's most well-known benefit is promoting regular bowel movements. It is also crucial to colon health. By adding bulk to stool and speeding up transit time, fiber helps flush out potential carcinogens more quickly, reducing the time harmful substances remain in contact with the intestinal lining.

The USDA recommends 25–34 grams of dietary fiber per day at a minimum, depending on age and sex. Yet the average American gets only 15 to 16 grams; barely half.

This isn't just a matter of digestion. Research links fiber to a reduced risk of colorectal cancer through multiple mechanisms:

Feeding beneficial gut bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which can inhibit tumor growth

Reducing inflammation and improving immune response in the gut

Binding and eliminating carcinogens, including harmful bile acids

Accelerating transit time, limiting the colon’s exposure to potential toxins

“Fiber helps reduce the risk of colorectal cancer — and several other cancers — through multiple mechanisms,” said Christina Fasulo, a registered dietitian with UCLA Health’s GI Nutrition Program. “When gut bacteria ferment fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which have anti-cancer properties, including inhibiting cell growth and promoting apoptosis in cancerous cells.”

A study led by Stanford geneticist Michael Snyder found that microbial fermentation of fiber modulates gene expression, activating tumor suppressors and suppressing genes linked to cancer growth. “We found a direct link between eating fiber and modulation of gene function that has anti-cancer effects,” Snyder said.

These benefits come mostly from whole plant foods: legumes, fruits, oats, vegetables, and whole grains. Added or "functional" fibers in processed foods don’t offer the same protection, despite marketing claims.

Who Gets Fiber — And Who Doesn’t

Fiber intake, like CRC risk, is uneven across demographics. Hispanic Americans average the highest fiber consumption (9.2g/1,000 calories), while Black Americans consume the least (7g/1,000 calories).

This tracks with CRC disparities: Black Americans are more likely to develop CRC at younger ages and have worse survival rates, even when diagnosed at the same stage.

And among low-income groups, older adults, and those without private insurance, fiber intake remains significantly below average.

The Fiber Supplement Trap

What about fiber powders, gummies, and bars? Some, like psyllium or inulin, can help with digestive regularity. But experts caution they shouldn’t replace real food.

Supplements lack the "matrix effect," which is the synergistic mix of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants found in whole plants. And in high doses, some can cause bloating or cramping.

More troubling are ultra-processed snacks labeled as "fiber-enriched." These often contain isolated fiber additives but remain high in sugar, fat, and sodium. Studies show they may create a "health halo" that misleads consumers while still raising chronic disease risk.

Colon Health Is Microbiome Health

When fiber is fermented in the colon, it fuels good bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. Butyrate, in particular, helps regulate inflammation and can stop tumor cells from multiplying.

“One important type of fiber is resistant starch… Fiber… acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial gut bacteria and producing short-chain fatty acids, like butyrate, that play a key role in reducing inflammation, protecting the gut lining and promoting healthy cell growth,” said Johannah Katz, a registered dietitian at EatingWell.

Diets low in fiber starve these microbes, weakening the gut barrier and increasing susceptibility to disease. Some research even shows low-fiber diets may shift gut bacteria to consume the gut’s protective mucus layer.

“It’s not just about what we eat. It’s about what our microbes eat. And fiber is their food,” Fasulo said.

Policy and Labeling: Still Behind the Science

The FDA recognizes fiber as a "nutrient of public health concern," but regulation hasn’t kept pace with marketing.

Many processed foods include added fiber to boost label appeal, yet offer little nutritional value overall. And while school meals, WIC, and SNAP programs aim to improve fiber access, disparities persist.

Meanwhile, critics warn of conflicts of interest in dietary guideline committees, particularly from USDA-affiliated agricultural promotion programs. Some scientists say this undermines efforts to prioritize fiber-rich plant foods over meat and dairy-heavy diets.

Everyday Shifts That Make a Difference

You don’t need to go vegan or count grams to improve your fiber intake. Here are some real-world strategies:

Mix it up: Add lentils or quinoa to white rice to double the fiber content.

Upgrade breakfast: Choose foods with 5g+ of fiber per serving. Add fruit and seeds to yogurt or oatmeal.

Use frozen and canned smartly: Beans, peas, berries, and artichokes retain fiber and nutrients.

Snack better: Swap chips for nuts, veggies, or unsweetened dried fruits.

Beware health halos: Don’t rely on processed bars or powders as your main source.

Final Take

The fiber gap isn’t just a diet issue. It’s a cancer risk multiplier, especially for younger generations and underserved communities.

Closing that gap could help reverse the rise in early-onset colorectal cancer. But it will take more than individual effort. It requires better policy, labeling reform, equitable access to real food, and public health messaging that matches the science.

Affiliate Links: Our Picks for Everyday Fiber Fixes

These are whole food staples we recommend (and personally use) to support better colon health:

Affiliate revenue supports The Health Signal’s independent reporting.